| BURNT CORN, ALABAMA | ||

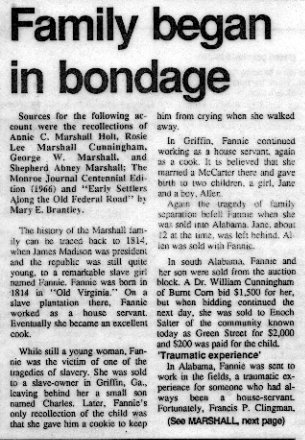

The Marshall family can be traced back to 1814 to Virginia, where Fannie Lee and Joe Lee, the parents of Nellie Lee, who married George Marshall. In Virginia, which she referred to as "Ole Virginny," Fannie had been a house slave. On the plantation there, she worked as a house servant, eventually becoming an excellent cook. While still a young woman, she was sold to a planter in Griffen, Georgia leaving behind her in Virginia, a small male child named Charles. She never saw this child again.

In Griffin, Georgia, Fannie continued as a house servant; her job was cooking. It is believed that she married a "McCarter" there and gave birth to two children, a girl named Jane and a boy named Allen

Fannie was again sold, this time into South Alabama. Jane, about twelve years old at the time, and was left behind. In Alabama, Fannie and her child, Allen, were put on the auction block. A Dr. William Cunningham of Burnt Corn bid $1500 for her, but the bidding continued the next day, she was sold to Enoch Salter of the Green Street Community for $2000 and $200 for the child, Allen.

Fannie was sent to work in the fields, a difficult experience for her because she had been a house slave. Fortunately for her, Francis P. Clingman, who owned a Boarding House in Burnt Corn hired her from Enoch Salter to work as a cook in the boarding house. Each morning Fannie walked from the Enoch Salter place near Green Street to Burnt Corn and each evening she returned, often to find little Allen hiding under the house to escape abuse.

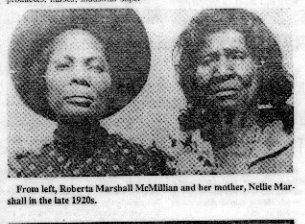

Fannie met and married Joe Lee and a baby girl whom they named Nellie was born to them shortly after slaves were freed what they called the "surrender." After the slaves were freed, Fannie continued to work for the Clingmans. She was responsible for buying groceries, preparing the food and paying the bills. Working for the Clingmans, Fannie lived frugally, saved, and purchased forty acres of land, which is still in the family today.

The defeated landowners sought to retain their free labor by devious means and by force. Fannie related one incident where she was taken from the house by hooded nightriders whose faces were blackened by soot to hide their identity. She was beaten by one of the riders, and each time his hand went up, a ring on his finger glistened in the darkness. A day or two later, Fannie recognized that ring on the finger of one of the diners at the boarding house. Fannie reported this information to her employer. The incident did not occur again.

Fannie, with the help of the Clingmans, worked diligently to contact the daughter that she had left behind in Georgia. Finally, she was able to contact her and they were reunited and Jane came to visit periodically. According to a granddaughter of Fannie, Jane was disappointed that she was not included in Fannie's will and she did not remain in touch with the family.

The Clingman's daughter, Nancy, was married to D.M. O'Brien, headmaster at Burnt Corn Academy. Their children, Bettie and Mary, taught Nellie to read, write, and "figure". At the age of fifteen, she passed the teachers' exam and was certified to teach in Alabama. She stated that one of the spelling words on the test that she was given was Conecuh.

Fannie was a member of the original Bethany Baptist Church at the time it was attended by black and whites. After the Civil War, the original church was sold to the black congregation and the white members built another church. Today there are two Bethany Baptist Churches in Burnt Corn.

Fannie never again saw or heard of or heard from her first born child, Charles that she was forced to leave behind in Virginia.

Fannie's daughter Jane that was left behind in Griffins, Georgia was reunited with her mother Fannie after the slaves were freed but remained in Georgia.

Fannie's other son

Fannie's youngest child Nellie went on and became a teacher and met and married George Marshall who was born in the final days of slavery in Flat Creek, Alabama, a community

Northwest of Burnt Corn in Monroe County.

George father was Bill Marshall, a plantation owner; his mother was Ann, a slave girl.

George often remarked that he was the only

one of the slave children who had shoes because his father was his "Master."

Nellie and George lived in Flat Creek for a year, then returned to Burnt Corn where they remained for life.

They built their first home closer to the town of Burnt Corn and was forced to move and then they built

another house which they lived in the rest of their lives.

They were industrious, frugal, and ambitious.

They were the parents of eleven children.

Childrens:

Their first house was a house right off the main street in Burnt Corn. A granddaughter, Theola Preyear, reared by her grandparents along with her siblings after the death of her father remembers living in the house now known as the Ellis house. Nellie, one daughter of Nellie and George's was married there in the house; she was called little Nellie, and she married John Henry Crook.

Nellie and George were pressured to sell the house because it was in town and was too close to the white neighbors. Theola Preyear remembered the day Herbert Ellis came and paid her grandparents for the house. He paid them in cash and she remembers them in the guest bedroom counting the money on the bed and chasing the children out lest they make a mistake.

Nellie and George then built another home, which is standing today and occupies the land that Fannie had brought.

The Marshall's were very much interested in education because they saw that it was a means of advancement. Two of their daughters Annie Coleman and Rosie Lee attended Tuskegee Institute and a son, George attended Fisk University. They attended these institutions to complete their education because the local schools at that time went only to the fourth or fifth grades.

Irene

Carlie

Johnnie

Roberta

Rosie Lee

Annie Coleman

James "Jimmy"

Nellie (Little Nellie)

George W.

Margaret "Maggie"

Pauline

Descendants of Nellie and George Marshall are scattered throughout the United states. Their occupations and professions includes doctors, politicians, college

professors, newspaper editors, teachers, ministers, TV reporter, producers, nurses, industrial supervisors, business persons, and farmers. The Marshall family

heritage is a rich and inspirational to all it's descendants

Irene

Carlie

Johnnie

Roberta

Rosie Lee

Annie Coleman

James "Jimmie"

Nellie

George W.

Maggie

Pauline

Irene, another daughter, married Jim Tait and remained in the community. Irene youngest daughter, Hettie (Irene), and grandson, Joseph (Sonny) Watson operate Watson's Burnt Corn Grocery Store in Burnt Corn. Some of the Watson Family remains in Burnt Corn today. Another grandson of Irene and son of Hettie, Vernon Watson, owns a television station in Pensacola, Florida. Maggie Preyear of Monroeville is another daughter of Irene.

Carlie, the second daughter of Nellie and George married William Osborne Abney of Monroe Station. One of their children, William "Pete" Abney, was a prominent farmer of Monroeville. Carlie's daughter, Shepard, who lives in Pensacola, remembers Fannies babysitting the great grandchildren.

Johnnie was the oldest son and third child of George and Nellie Marshall. He attended Fisk University and played ball for the school and worked

as railroad car porter while in college When he left college he married Carlie Robbins in 1913

Roberta also attended Tuskegee Institute, she later married Charles Ridgill; after his death, she married Ezell McMillan. Roberta's descentants include college professors and doctors. Her daughter Theola Preyear resided in Monroeville, Alabama.

Rosie Lee married Sidney Cunningham and they remained in the Burnt Corn community and farmed for a living.

Annie Coleman who attended Tuskegee Institute married Tom Holt and they were successful farmers and lived in the Burnt Corn Community until in their nineties when they went to live with a daughter in Akron, Ohio. Tom passed away in 1995 at the age of 104. Annie, passed in 1997 at the age of 105.

Jimmy, married Lorene Lee and reared his family in Burnt Corn.

Nellie and her husband John Henry Crook, moved to Akron, Ohio along with the youngest daughter

George and Nellie's youngest son, George W. Marshall married Donnie Crook, moved to Cincinnati.

Margaret (Maggie), one of the daughters married George Powers and moved to New York.

Pauline who married Fate McMillan the brother of Ezell McMillan.

They made their home in Akron, Ohio.

BACK TO MAIN PAGE